963 阅读 2020-08-24 09:28:02 上传

以下文章来源于 宏观语言学

Section Ⅰ Multilingual Speech Communities

Chapter 2: Language choice in multilingual communities

■ Choosing your variety or code

□ What is your linguistic repertoire?

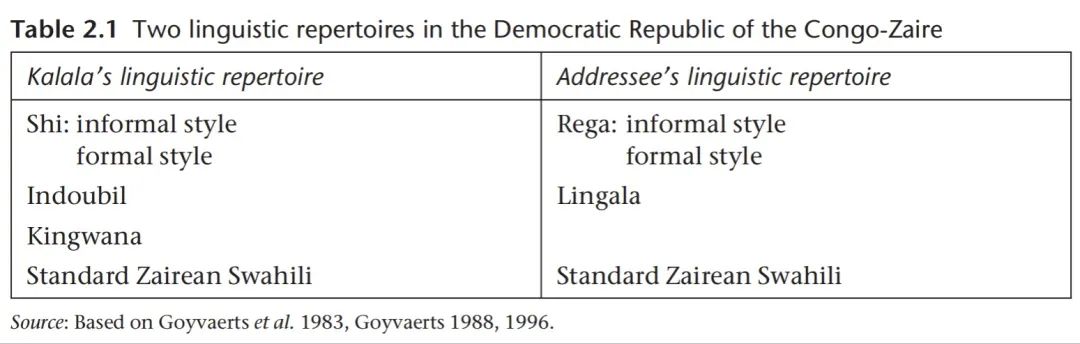

A polyglot’s experience in using languages is put in this part, in order to prove that the factors that lead Kalala to use one code rather than another are the kinds of social factors identified in the previous chapter as relevant to language choice in speech communities throughout the world. Characteristics of the users or participants are relevant. (Janet Holmes 2013: 20)

□ Domains of language use

# Certain social factors – who you are talking to, the social context of the talk, the function and topic of the discussion – turn out to be important in accounting for language choice in many different kinds of speech community. (Janet Holmes 2013: 21)

# Domains of language use, a term popularised by Joshua Fishman, an American sociolinguist. A domain involves typical interactions between typical participants in typical settings. (Janet Holmes 2013: 22)

# The term variety includes different dialects and styles of language.

# A study by Joan Rubin in the 1960s identified complementary patterns of language use in different domains. (Janet Holmes 2013: 22)

■ Modelling variety or code choice

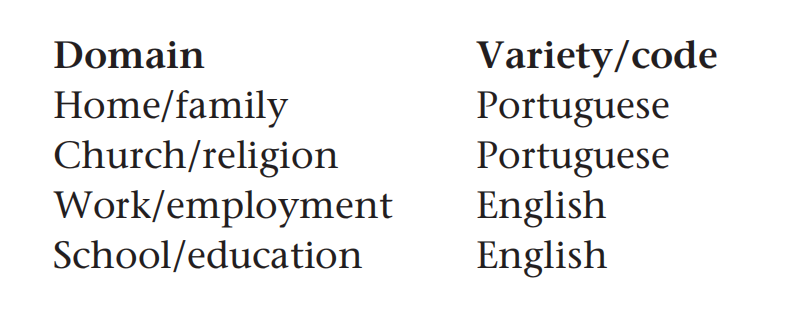

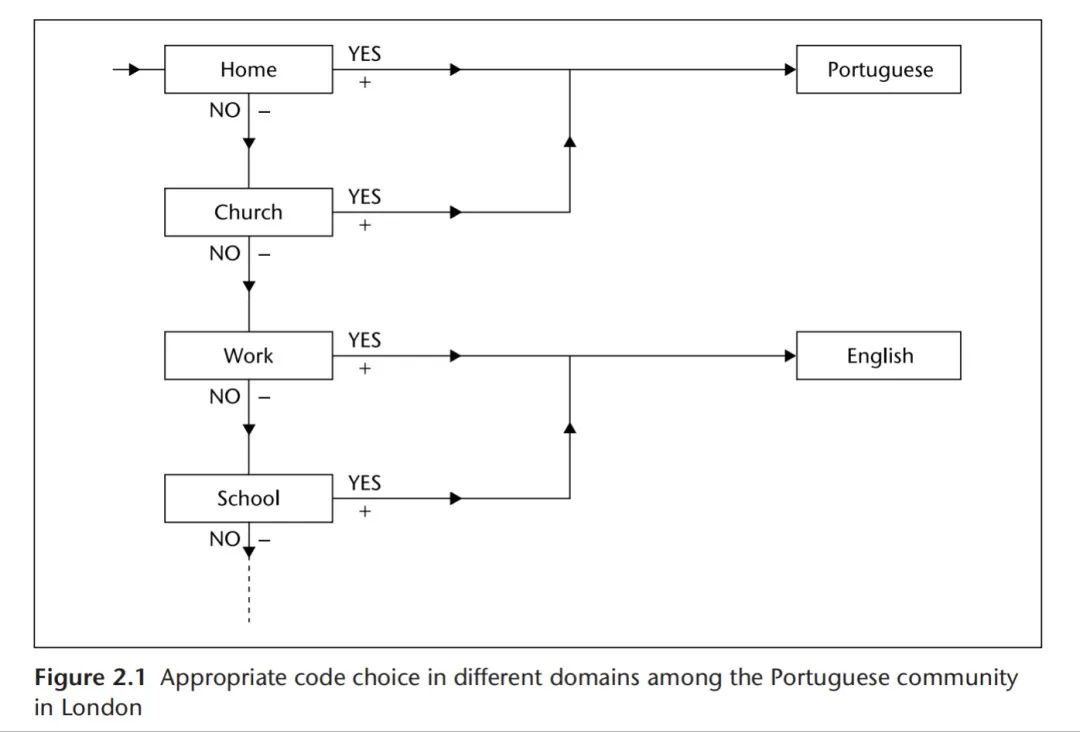

Domain is clearly a very general concept which draws on three important social factors in code choice – participants, setting and topic. It is useful for capturing broad generalizations about any speech community. Using information about the domains of use in a community, it is possible to draw a very simple model summarizing the norms of language use for the community. This is often particularly useful for bilingual and multilingual speech communities. (Janet Holmes 2013: 23)

# Two advantages of this model:

1) First it forces us to be very clear about which domains and varieties are relevant to language choice.

----The model summarizes what we know about the patterns of language use in the community. It is not an account of the choices a person must make or of the process they go through in selecting a code. It is simply a description of the community’s norms which can be altered or added to if we discover more information.

2) Secondly it provides a clear basis for comparing patterns of code choice in different speech communities.

----Models make it easy to compare the varieties appropriate in similar domains in different speech communities. And a model is also useful to a newcomer in a community as a summary of the appropriate patterns of code use in the community. A model describes which code or codes are usually selected for use in different situations. (Janet Holmes 2013: 24)

@ The limitations of a domain-based approach to language choice.

----The domain-based approach allows for only one choice of language per domain, namely the language used most of the time in that domain. Clearly more than one language may occur in any domain. Different people may use different languages in the same domain. We will see below that for a variety of reasons (such as who they are talking to) the same person may also use different languages in the same domain. (Janet Holmes 2013: 47)

□ Other social factors affecting code choice

The components of a domain do not always fit with each other. They are not always ‘congruent’. ... People may select a particular variety or code because it makes it easier to discuss a particular topic, regardless of where they are speaking. ... Some describe this as ‘leakage’, while in fact, it is quite normal and very common. Particular topics may regularly be discussed in one code rather than another, regardless of the setting or addressee. (Janet Holmes 2013: 25)

1) The social distance dimension

2) The status relationship

# Typical role relationships are teacher–pupil, doctor–patient, soldier–civilian, priest–parishioner, official–citizen. The first-named role is often the more statusful.

3) The dimension of formality

4) The function or goal of the interaction

----In describing the patterns of code use of particular communities, the relevant social factors may not fi t neatly into institutionalized domains.

----The only limitation is one of usefulness. If a model gets too complicated and includes too many specific points, it loses its value as a method of capturing generalizations. (Janet Holmes 2013: 26)

# Models can usefully go beyond the social factors.

# Because they are concerned to capture broad generalizations, there are obvious limits to the usefulness of such models in describing the complexities of language choice. (Janet Holmes 2013: 26)

# Interactions where people switch between codes within a domain cannot always be captured. (Janet Holmes 2013: 27)

■ Diglossia 双语现象/ 双重语体

□ A linguistic division of labour

Diglossia:In the narrow and original sense of the term, diglossia has

three crucial features:

1. Two distinct varieties of the same language are used in the community, with one regardedas a high (or H) variety and the other a low (or L) variety.

2. Each variety is used for quite distinct functions; H and L complement each other.

3. No one uses the H variety in everyday conversation.

# In these communities, while the two varieties are (or were) linguistically related, the relationship is closer in some cases than others. (Janet Holmes 2013: 27)

# The degree of difference in the pronunciation of H and L varies from place to place; ... The grammar of the two linguistically related varieties differs too. Often the grammar of H is morphologically more complicated. (Janet Holmes 2013: 27-28)

# No one uses H for everyday interaction. (well, I doubt it... such as Sheldon in TBBT, who uses terminology almost all day long with nearly everyone he meets.)

# It would be a bit like asking for steaks at the butcher’s using Shakespearian English.

□ Attitudes to H vs L in a diglossia situation

# It has prestige in the sense of high status. These attitudes are reinforced by the fact that the H variety is the one which is described and ‘fixed’, or standardized, in grammar books and dictionaries.

# However, attitudes to the L variety are varied and often ambivalent.

# (from exercise) Summarize what you now know about the differences between H and L in diglossic communities. (Janet Holmes 2013: 29)

□ Diglossia with and without bilingualism

# Diglossia is a characteristic of speech communities rather than individuals.

# The term diglossia describes societal or institutionalized bilingualism, where two varieties are required to cover all the community’s domains. (Janet Holmes 2013: 30)

1) Box 1 refers to a situation where the society is diglossic, two languages are required to cover the full range of domains, and (most) individuals are bilingual. (Bislama, the lingua franca of Vanuatu)

2) Box 2 describes situations where individuals are bilingual, but there is no community-wide functional differentiation in the use of their languages. (many English speaking countries)

3) Box 3 describes the situation of politically united groups where two languages are used for different functions, but by largely different speech communities. (some colonized countries with clear-cut social class divisions)

4) Box 4 describes the situation of monolingual groups, and Fishman suggests this is typical of isolated ethnic communities where there is little contact with other linguistic groups. (Iceland, especially before the 20th century) (Janet Holmes 2013: 30)

□ Extending the scope of ‘diglossia’

----‘Diglossia’ is here being used in a broader sense which gives most weight to feature or criterion:

(ii) – the complementary functions of two varieties or codes in a community.

Features (i) and (iii) are dispensed with and the term diglossia is generalized to cover any situation where two languages are used for different functions in a speech community, especially where one language is used for H functions and the other for L functions. There is a division of labour between the languages. (Janet Holmes 2013: 31)

□ Polyglossia

# The term polyglossia has been used for situations like this where a community regularly uses more than three languages.

# Polyglossia is thus a useful term for describing situations where a number of distinct codes or varieties are used for clearly distinct purposes or in clearly distinguishable situations. (Janet Holmes 2013: 32)

□ Changes in a diglossia situation

# Diglossia has been described as a stable situation. It is possible for two varieties to continue to exist side by side for centuries;

# Alternatively, one variety may gradually displace the other.

Eg. English vs. French in England after 1066;

Greece: Dhimotiki (L) vs. Katharevousa (H); (Janet Holmes 2013: 32-33)

# Finally, it is worth considering whether the term diglossia or perhaps polyglossia should be used to describe complementary code use in all communities.

--In multilingual situations, the codes selected are generally distinct languages.

--In predominantly monolingual speech communities, ... the contrasting codes are different styles of one language.

# In some cases, the situation could be described as triglossic rather than diglossic. (Janet Holmes 2013: 34)

(From exercise: How can the following three dimensions be used to distinguish between H and L varieties in a diglossic speech community?)

■ Code-switching or code-mixing

□ Participants, solidarity and status

# A code-switch may be related to a particular participant or addressee.

# A speaker may similarly switch to another language as a signal of group membership and shared ethnicity with an addressee.

# Such switches are often very short and they are made primarily for

social reasons – to signal and actively construct the speaker’s ethnic identity and solidarity with the addressee.

# Emblematic switching or tag switching.

The switch is simply an interjection or a linguistic tag in the other language which serves as an ethnic identity marker.

# A tag contributing to the construction of solidarity, switches can also

distance a speaker from those they are talking to. (Janet Holmes 2013: 35)

# Different kinds of relationships are often expressed or actively constructed through the use of different varieties or codes.

# Situational switching: When people switch from one code to another for reasons which can be clearly identified, it is sometimes called situational switching. (Janet Holmes 2013: 36)

□ Topic

# Bilinguals often find it easier to discuss particular topics in one code rather than another.

# For many bilinguals, certain kinds of referential content are more appropriately or more easily expressed in one language than the other.

# A referentially oriented code-switch may happen when a speaker switches code to quote a person.

# A related reason for switching is to quote a proverb or a well-known saying in another language.

(Janet Holmes 2013: 37)

□ Switching for affective functions

# Many bilinguals and multilinguals are adept at exploiting the rhetorical possibilities of their linguistic repertoires. (Janet Holmes 2013: 39)

# A language switch in the opposite direction, from the L to the H variety, is often used to express disapproval. (Janet Holmes 2013: 39)

□ Metaphorical switching

# In certain situation, there are no obvious explanatory factors accounting for the specific switches between two language varieties used. (Janet Holmes 2013: 41)

# Metaphorical switching: Each of the codes represents or symbolizes a set of social meanings, and the speaker draws on the associations of each, just as people use metaphors to represent complex meanings. The term also reflects the fact that this kind of switching involves rhetorical skill. Skilful code-switching operates like metaphor to enrich the communication. (Janet Holmes 2013: 42)

# Code-mixing suggests the speaker is mixing up codes indiscriminately or perhaps because of incompetence, whereas the switches are very well motivated in relation to the symbolic or social meanings of the two codes. (Janet Holmes 2013: 42)

# It is not always possible to account for choices among languages in situations where the participants are all multilingual. (Janet Holmes 2013: 43)

□ Lexical borrowing

# Lack of vocabulary:When speaking a second language, for instance, people will often use a term from their mother tongue or first language because they don’t know the appropriate word in their second language.

# People may also borrow words from another language to express aconcept or describe an object for which there is no obvious word available in the language they are using. Borrowing of this kind generally involves single words – mainly nouns – and it is motivated by lexical need.

# Borrowings often differ from code-switches in form too. Borrowed words are usually adapted to the speaker’s first language. They are pronounced and used grammatically as if they were part of the speaker’s first language.

(Janet Holmes 2013: 43)

# By contrast, people who are rapidly code-switching – as opposed to borrowing the odd word – tend to switch completely between two linguistic systems – sounds, grammar and vocabulary. (Janet Holmes 2013: 44)

□ Linguistic constraints

# Some believe there are very general rules for switching which apply to all switching behaviour regardless of the codes or varieties involved. They are searching for universal linguistic constraints on switching. (Janet Holmes 2013: 44)

# ‘the equivalence constraint’: It has been suggested for example that switches only occur within sentences ( intra-sentential switching ) at points where the grammars of both languages match each other. (Janet Holmes 2013: 44-45)

# A ‘matrix language frame’ (MLF) imposes structural constraints on code-switched utterances.

# Other sociolinguists argue that it is unlikely that there are universal and absolute rules of this kind. It is more likely that these rules simply indicate the limited amount of data which has been examined so far.

----They also criticize the extreme complexity of some of the rules, and point to the large numbers of exceptions.

----These sociolinguists argue for greater attention to social, stylistic and contextual factors. The points at which people switch codes are likely to vary according to many different factors, such as which codes are involved, the functions of the particular switch and the level of proficiency in each code of the people switching.

(Janet Holmes 2013: 45)

□ Attitudes to code-switching

# People are often unaware of the fact that they code-switch.

# Reactions to code-switching styles are negative in many communities, despite the fact that proficiency in intra-sentential code-switching requires good control of both codes. (Janet Holmes 2013: 46)

Summary

In this chapter, the focus has moved from macro-level sociolinguistic patterns and norms observable in multilingual and bilingual contexts, to micro-level interactions between individuals in these contexts. Individuals draw on their knowledge of the norms when they talk to one another. They may choose to conform to them and follow the majority pattern, using the H variety when giving a formal lecture, for example. Or they may decide to challenge the norms and sow the seeds of potential change, writing poetry in the L variety, for instance.

People also draw on their knowledge of sociolinguistic patterns and their social meanings when they code-switch within a particular domain. Skilful communicators may dynamically construct many different facets of their social identities in interaction. (Janet Holmes 2013: 46)

■ Concepts introduced

Domain

Diglossia

H and L varieties

Bilingualism with and without diglossia

Polyglossia

Code-switching

Situational switching

Metaphorical switching

Code-mixing

Fused lect

Lexical borrowing

Intra-sentential code-switching

Embedded and matrix language

Inter-sentential code-switching

相关工具